My Hope and Inspiration

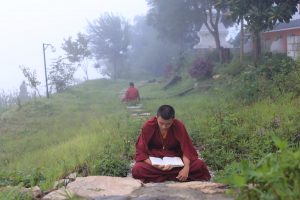

Many people have asked me how we came to have children in the retreat centre. It started in 2017 when I accepted an invitation to teach in Zimbabwe, at Kagyu Samye Ling Zimbabwe, and a small group of Buddhists from the Congo travelled to hear me teach; if you can call my talks ‘teachings’ that is.

I could hardly believe that they would travel all that way just to see me. The distance from Lubumbashi in the south of D.R.Congo to Harare, Zimbabwe, is over a thousand kilometres, more than 24 hours by bus, with two border crossings to negotiate.

In general when someone comes to see me seeking advice etc, I feel a certain obligation to that person; because they come with the hope that I will be able to help them. And I too hope and pray that I might be able to fulfil their hopes.

I was really moved by the faith in the dharma that they had demonstrated in the effort and expense (partially covered by the kind help of some members of Kagyu Samye Ling Zimbabwe, I should add) that they had expended to come to see me, and simply could not send them away without having done my best to help them in some meaningful way. Their faith was also totally natural and took its own joyful expression.

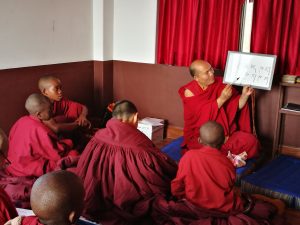

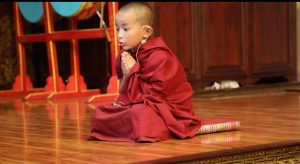

Towards the end of my stay they came to see me as a group and asked what they could do to further the spread of dharma in their centre, city and country. I replied that if they were really keen for the dharma to take root in the Congo and Africa then they would need their own people to become learned and well-practised in the dharma, and essentially to have been immersed in it from a young age– that they could not continue to rely on people coming from the outside to propagate the dharma.

Needless to say the same is true for any country and continent, but especially for poorer countries, because the inescapable fact is that most lamas don’t seem keen to travel to such places.

Anyway, I said that if they were interested I would be willing to oversee the education and dharma training of 3 or 4 children of families connected to their dharma centre. They seemed over the moon and very excited at the prospect. I told them to not decide there and then but to go home and think about it and let me know. I also explained that the children must be joined by one adult who can teach them their native tongue and culture, otherwise they would end up becoming foreigners to their own land and people, which would defeat the object.

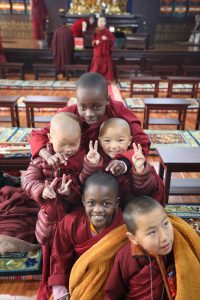

They responded soon after they had arrived home, saying there were five children (3 boys and 2 girls) who wanted to come to Nepal, together with one adult, a father of one of the children. I wasn’t sure whether I’d have the resources to cover the living expenses, visa fees, travel fees etc for six people, but the prospect of refusing one of the children and the impact that would have on their life prospects wasn’t something I could contemplate. So I agreed, with trust in the Three Jewels that all would work out one way or another.

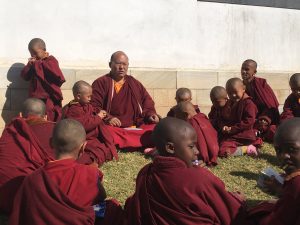

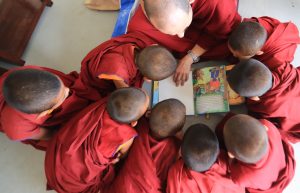

Not long after they had arrived in the retreat centre, the Lord of Refuge, Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche, asked whether he could send some young monks from the gompa to live and study here. Naturally, it being the Lama’s wish, I agreed immediately. After all, this is Thrangu Gompa’s retreat centre, not my retreat centre. Rinpoche said he would ask the headmaster of the monastery school to hand-pick five of the most promising young monks. I’m not sure that it happened like that in the end, but five young monks (12-13 years old) were sent here. Not long after they had arrived, I received several phone calls from a child begging to come to the retreat centre, he was devastated not to have been selected. I asked how he had got my number and whose phone he was using to call, and it seems he had found my number among a list of telephone numbers of Thrangu Gompa staff members at the back of a Thrangu Gompa booklet, and he had asked to borrow the phone of older friend. I made some enquiries to make sure that there wasn’t some uncle or other relative coercing him, but it seems he really did contact me under his own steam; so I let him come.

After that the flood-gates opened somewhat and we now have over 30 children in the retreat centre. Funnily, when the Thrangu Gompa retreat centre first moved here [just outside Bhaktapur at a Milarepa practice site], from Namo Buddha, almost 20 years ago, Thrangu Rinpoche planned to have some children here, but the retreatants thought that having kids running around would be an obstacle to the practice.

At one point a year or two ago, I had it in mind to have children here from all parts of the world with the hope that this would not only benefit them personally but that they would eventually carry the precious dharma back to their own countries and peoples. It is clear now that this wish will not come to pass. Although we do have children from quite a few countries, we still do not have any Western children, which is a shame, as I would’ve very much welcomed them. However, most Western Buddhists continue to place their faith more in Western values and institutions than Buddhist ones. You can understand non-Buddhists holding that mindset, but one might expect Buddhists to have a different perspective.

For example, some Western Buddhists tried to stop the African from children coming here, many were critical of it, and some had the most horrible things to say about it and about me in particular. I understand that everyone has their own ways of seeing things but I find it difficult to understand why they would interfere, thinking that they know better than the children’s own parents – it’s not as if those who were opposed to the children coming here are so concerned for the well-being of the children that they would look after the children themselves, out of their own pocket. Also they would not have known anything about the kind of environment the children would be coming to, or the education and general care they’d receive.

My view is that while we will do all we can to enable the children to become exceptionally learned and advanced practitioners, at the very least they will never go hungry or cold, and will gain a very decent level of education by anyone’s standards. So I’m absolutely certain that they will not lose out from being here. I’ve seen where the children come from, I have visited their family homes and have a good idea of the types of future they could expect if they were to have remained and grown up there. It is not at all unusual for parents of children in developing countries to send a child away to be educated. But some people think their way is the best and only way and try to impose that on others without knowing anything of the situation or context.

I have told the parents of some of the children, “I cannot guarantee that your child will become an accomplished practitioner or a great lama, but I can guarantee that if your child is living here they will reach adulthood with a healthy mind.” In today’s world I think that this is quite a difficult claim to make, but I stand by it because you can hardly find anyone who grew up in this sort of environment that suffers from depression and the like.

I’m fully aware that I will probably not live to see the children grown up and in their prime, hopefully doing tremendous amounts of good in the world, but whether I see it or not is of little importance. From my side, what’s important is that I do all I can to give these children the best opportunity to study and practise the dharma, as this is the most effective way that I think I can help others and aid the longevity of the buddha dharma.

The children we have here in the retreat centre are my hope and inspiration for the future. They are very close to my heart. If just one child turns out well… one person can achieve amazing things.

(A selection of transcripts from talks given by Drupon Khen Rinpoche in the Summer of 2021, together with some older and more recent photos.)